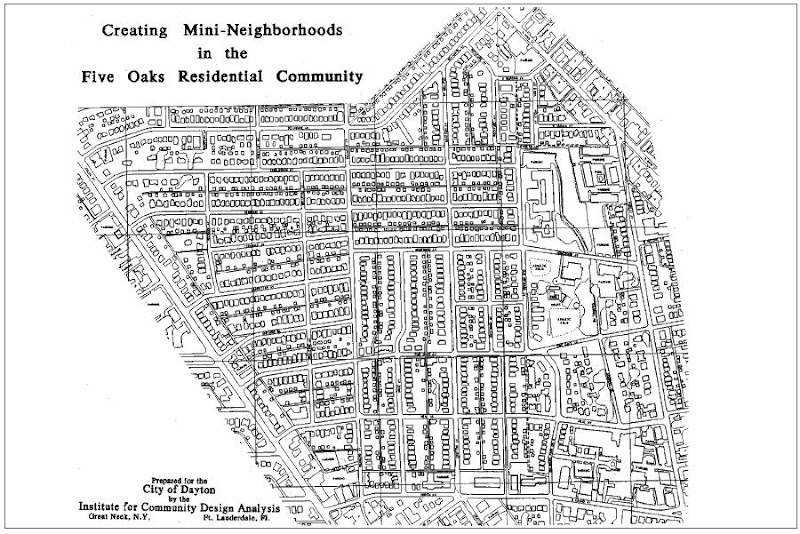

Plan of original layout of Five Oaks

Five Oaks consisted of about 2,000 households with different types of one- and two-family row housing in a rectilinear grid layout near the downtown area of Dayton, Ohio.

The City of Dayton asked Oscar Newman to apply the "Defensible Space" concept to the Five Oaks neighbourhood. Working with the community and city staff, he reorganized Five Oaks into 10 mini neighbourhoods: cul-de-sac streets with gates to block the heavy through-traffic that had plagued the area.

The changes were to accomplish a few important things: remove vehicular through-traffic completely; completely change the character of the streets (instead of being long, directional avenues laden with traffic, become places where children could safely play and neighbours interact); define the mini-neighbourhood streets as being under the control of the residents, and fewer cars would mean easier recognition of neighbours – and strangers. Access to the newly-defined mini-neighbourhoods, composed of from three to six streets, would be limited to one entry portal off an arterial street.

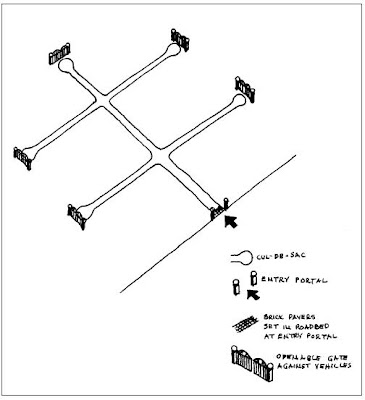

Portal as designed

Portal as built

Limiting access and egress to one opening would mean that criminals and their clients would have to enter a small mini-neighbourhood to transact their business, and they would have to leave it the same way they came in. There would no longer be a multitude of escape routes. A call to the police by residents would mean that criminals would meet police on their way out. It was reasoned that such a street system would be perceived by criminals as too risky.

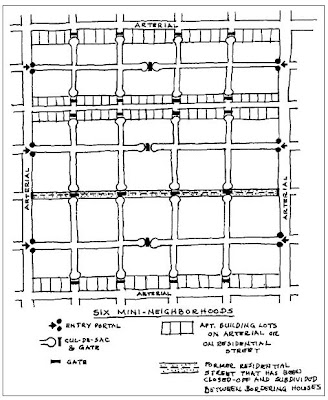

Gates defined the neighbourhood boundary

The subdivision of a community into mini-neighbourhoods was intended to encourage the interaction of neighbours. Parents watch their children playing in the now quiet streets and get to know each other. They no longer feel locked in their houses, facing the world alone.

Community Participation in Designing Mini-Neighbourhoods

As many people as possible were invited to participate in defining the boundaries of their mini-neighbourhoods, that is, in deciding which streets should remain open and where the gates should go up. At a community meeting to plan the mini-neighbourhoods in Five Oaks, residents took turns marking on a map what they thought of as their mini-neighbourhoods, according to the following principles:

- Smallness is essential to identity, so a mini-neighbourhood should consist of a grouping of no more than three to six streets. The optimal configuration for a mini-neighbourhood is a Greek cross, a vertical with two horizontals. Only one point of the cross will remain open, the other five will have gates across them.

- Cul-de-sac configurations should not be too large, for they take residents too far out of their way and produce too much of their own internal traffic.

- A mini-neighbourhood should consist of a grouping of streets sharing similar housing characteristics: building type (such as detached, semi-detached, row houses, and walk-ups), building size, lot size, setbacks from the street, building materials, architectural style and density.

- To facilitate access by emergency vehicles, access to the entry portal of each mini-neighbourhood should be from existing arterial streets. As much as possible, these arterials should be on the border of the Five Oaks community to enable outsiders to find their way in easily.

- Mini-neighbourhoods and their access arterials should be designed to facilitate access but discourage through-traffic.

Mini-neighbourhood

Mini neighbourhoods

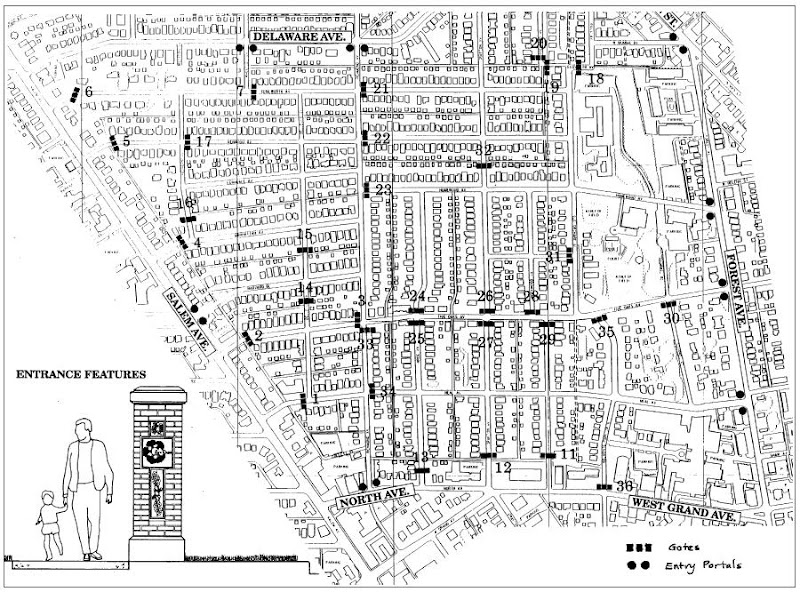

Layout Plan of Five oaks after change

Altogether, 35 streets and 25 alleys were closed in Five Oaks. The major arterials that defined the periphery of the community were retained intact and allowed east-west and north-south movement past the community.

Results: Reduction in Crime

Within the next two years, overall crime fell by 25 percent and violent crime by 50 percent, according to the city's Office of Management and Budget. Traffic was reduced by 67 percent, and traffic accidents by 40 percent. Robbery, burglary, assault, and auto theft were found to be the lowest in five years, while crime had increased 1 percent in Dayton overall. Individual families' investment in their homes had substantially increased, and for the first time in many years, houses in the neighbourhood were attracting families with children.

Increase in the Value of Homes

Along with reductions in crime, housing sales increased by 55 percent and housing values increased by 15 percent, compared to 4 percent in the region.

People started upgrading their houses

Peopled Felt Safer

In addition to the data collected by the city, a survey of residents by the University of Dayton before the changes and afterwards found that 53 percent thought there was less crime, and 61 percent thought the neighbourhood was a better place to live in. Drug-dealing, theft from houses and cars, and harassment were each found to be less of a problem than it had been a year previously. Most importantly, there was no difference in the perception of change between whites and blacks or between renters and homeowners.

Crime did not just move elsewhere

The usual complaint about such programs, that they displace crime into the surrounding neighbourhoods, proved untrue. Crime in the surrounding communities decreased 1.2 percent. The police explain this saying that the perception among criminals is that the residents of Five Oaks have taken control of their streets, and because the criminals and their clients don't know the neighbourhood's exact boundaries, they have moved out of the surrounding area as well. The positive effects of the Five Oaks section spilled over into the bordering communities – some of whom are now adopting a similar restructuring.

Cost Effectiveness

The entire cost of this project was USD693,375 – approximately USD10,000 per street. In effect, the increase in value of just one home in one year, on a street of 30 homes, paid for the cost of that street closure.

Sense of community

Five Oaks demonstrated that once people come together within their own mini-neighbourhood, they reach out to other neighbourhoods and to the larger urban community. In other cities, mini-neighbourhood plans have not only arrested decline; they have made people realize they could be effective in intervening to change things. It has also led them to become active in city politics.

Children played on the streets.

Excerpted from Oscar Newman, “Defensible Space”, Shelteronline

Related Post: |

Social Bookmarking

1 comment:

I have seen this put into effect before and always wondered why they did this to certain areas. Now I know! :)

Kyle

Post a Comment