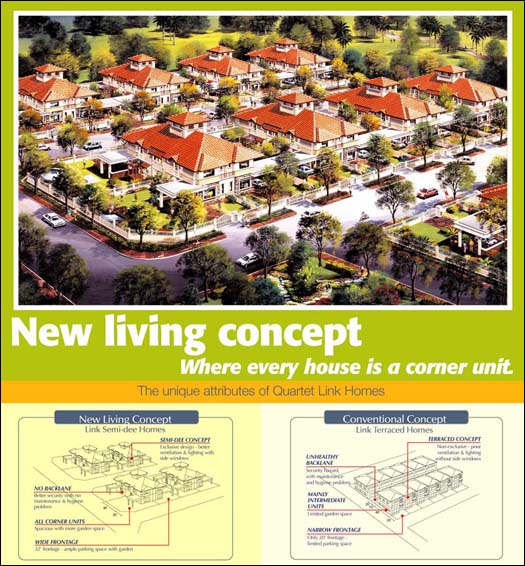

Another trip I made with my children was to a fast-growing town in the northern State of Kedah. Sungei Petani on first acquantance looks like a sprawling, prosperous but uninteresting town that has been benefitting from the spill-over of economic development in neighbouring Penang, about 30km south. The project that I am involved with as architect seeks to benefit from that growth.

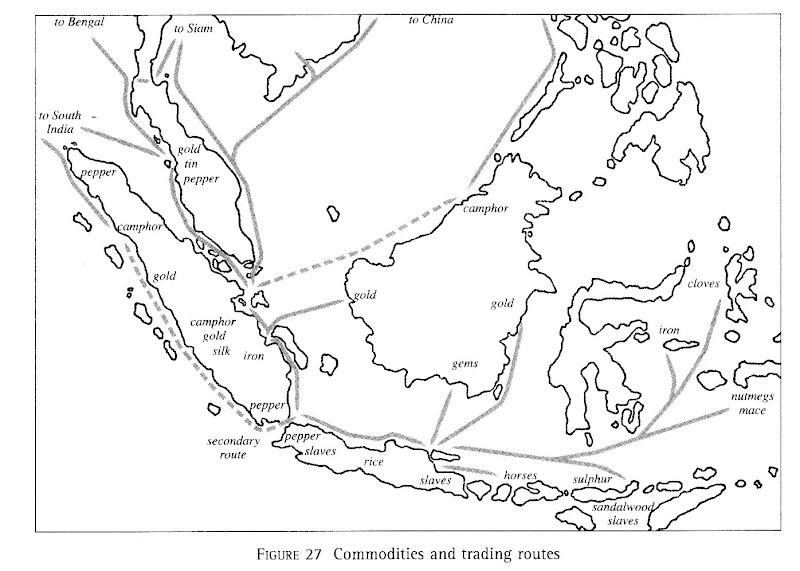

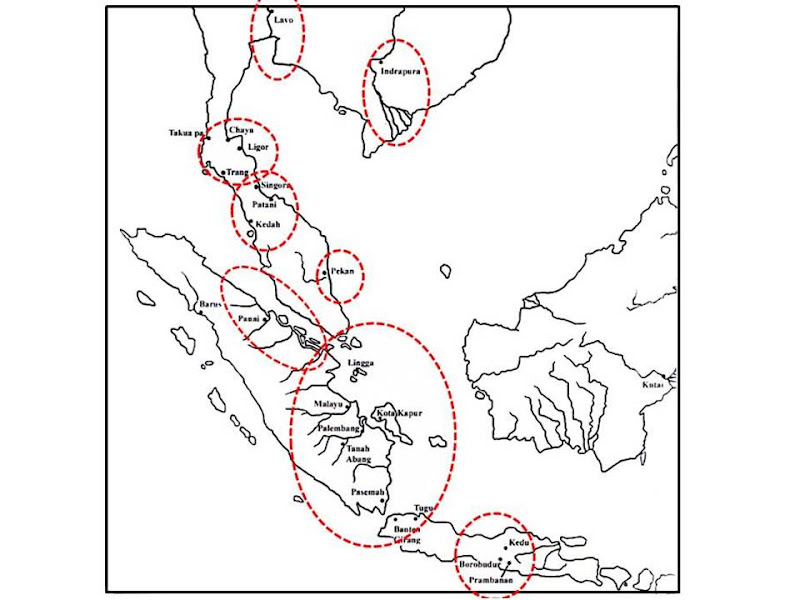

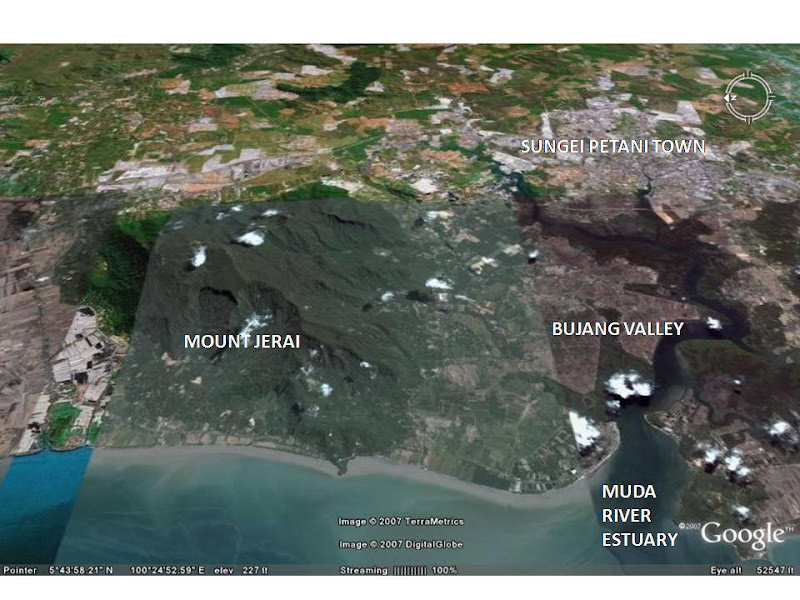

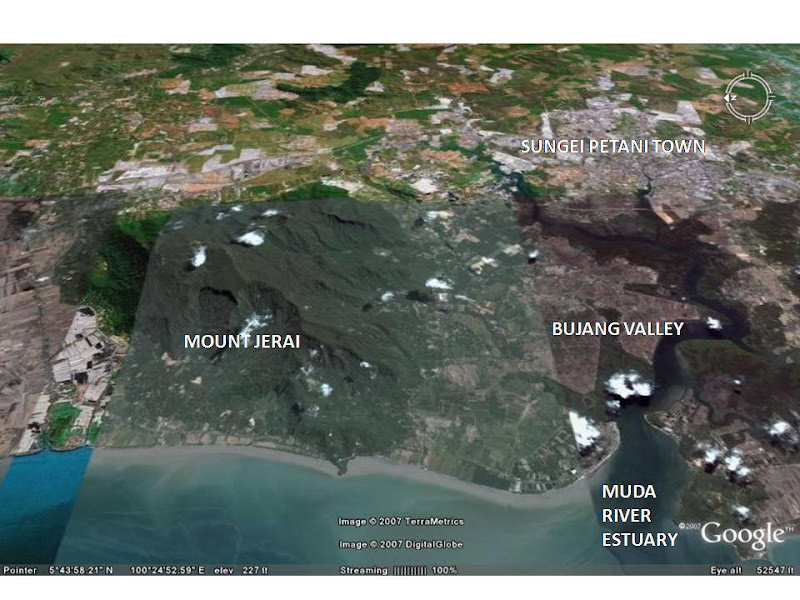

But in fact the town is more than just a would-be suburb of Penang. It is located near the Muda river estuary at the foot of Mount Jerai, which dominates the flat plain that surrounds it. Archeological finds in the Muda river and its tributaries has confirmed the area around Sungei Petani as the site of an ancient Malay port called

Kadaram by the Indians and referred to as

Ke-da by Chinese Annals.

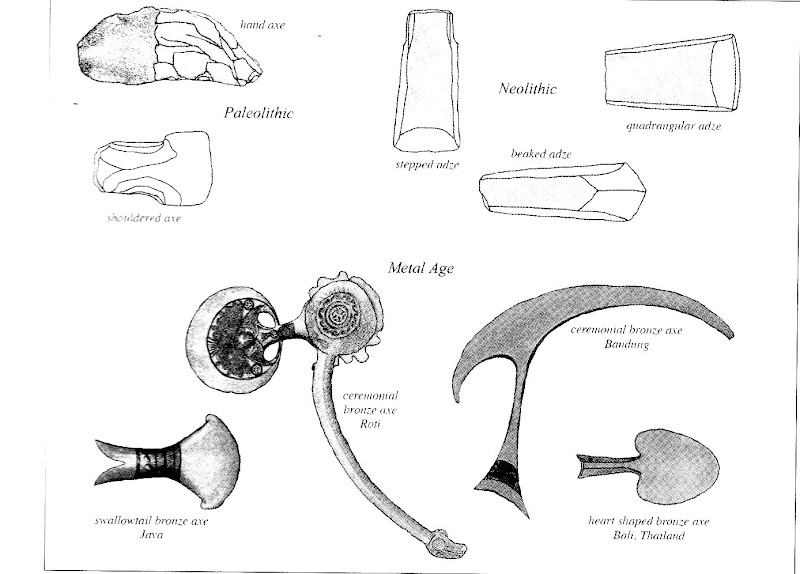

When I was in school 40 years ago, we learned that the early Malays walked down from an area around South China (the area around present day Kunming) following from the proto-Malays. The first and greatest Malay civilization was in Melaka dating from the 14th Century BC. There has been considerable revision since then.

Kedah preceded Melaka by as much as 14 centuries. Several of the archeological finds have been collected, reconstructed and displayed at the Lembah Bujang Archeological Museum on the foothills of Mount Jerai.

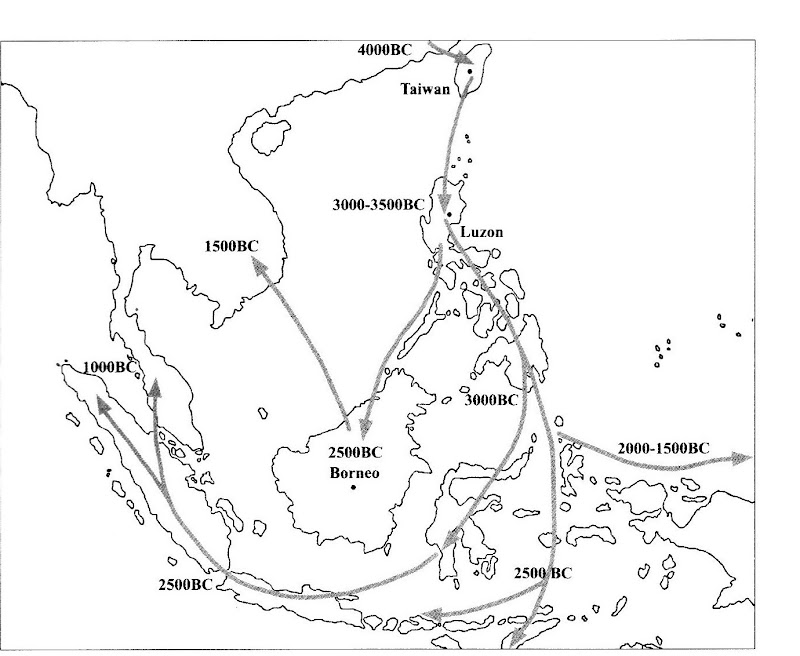

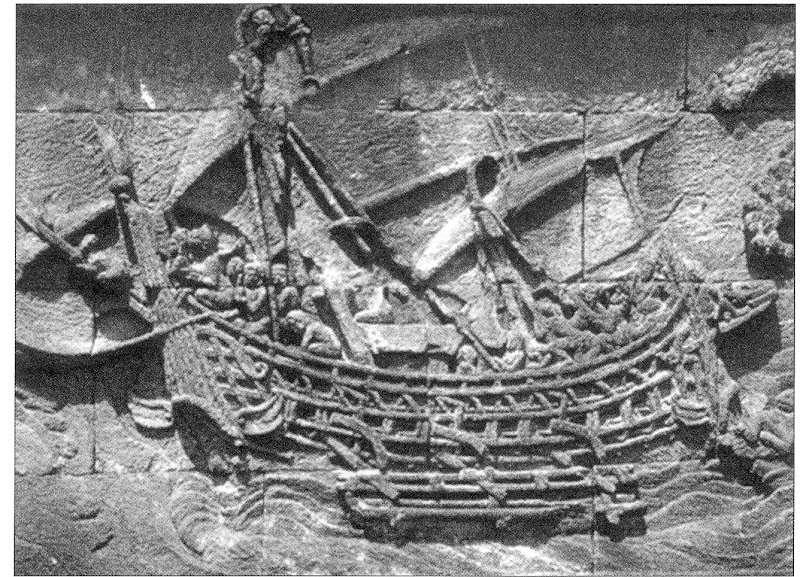

At the entrance of the indoor gallery are what look like dugout canoes, but are believed to have used sails as well. This is the core technology that brought the ancestors of the the Malays from South China to Malaysia by way of the

Chang Jiang (the Yangtze River), Taiwan, Phillipines and Borneo. However, the dating of some of these timber boats from the first millenium AD (found on the museum notes) seems a bit incredulous to me!

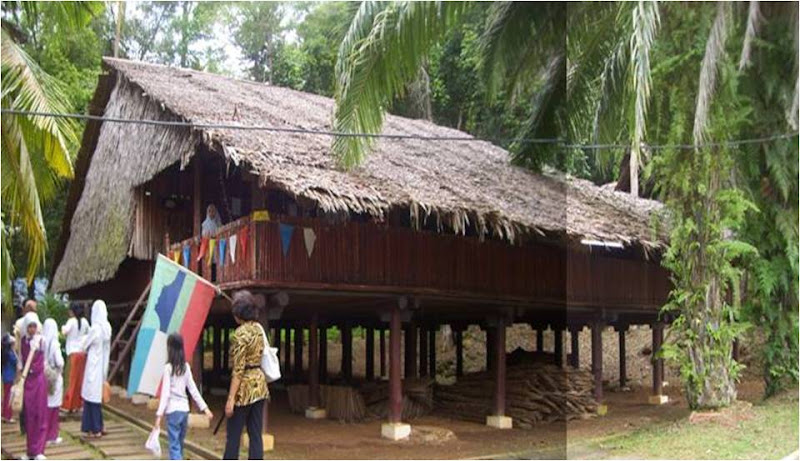

That is the problem with archaeology in the hot and humid equatorial climate of South East Asia. Timber was the most convenient material for construction, but wood cannot withstand the effects of rot and insect attack. I’ve been told, though, that being submerged in water and in some way deprived of oxygen can preserve some hard-woods.

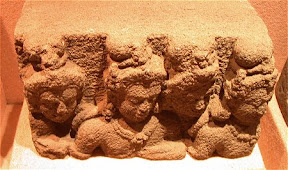

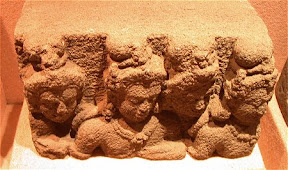

In the indoor gallery are plenty of beads of stones and glass, and ceramic pots that attest to Kedah as a trading port. There are also bits of shrines - some Hindu, some Bhuddist – stone statues, inscriptions in Indian script, granite column base, column sections, clay roof tiles and stone footings for long disintegrated timber posts.

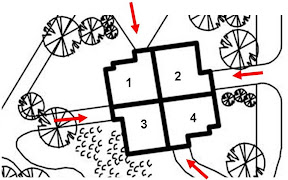

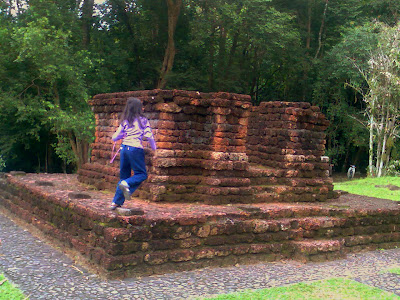

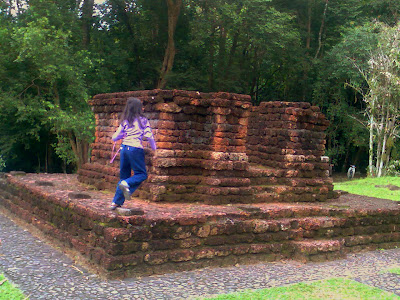

There is an external gallery where the base of some of the ancient shrines have been reconstructed. Some of these were made with granite and local stone, blending in with the stone boulders and outcrops of Mount Jerai. But others used laterite blocks, a softer and courser material.

One shrine used clay bricks with detailed corbels and recesses. These were believed to have been imported.

Only the base have been rebuilt, not the columns and the roof. But the stone footings for the timber columns have been put in place and you can just about imagine how these shrines could have looked like.

Right next to the museum grounds is a stream that rushes down a stretch of bare stone outcrop. This was where we rested our tired feet. If we had time and energy we could have continued up a trek to the peak of Mount Jerai , but that had to wait until my girls grow up a bit more.

For hotels and other things to do in Kedah, refer to

Kedah HotelsTechnorati Tags:Malaysian Architect,Malaysian History, Early Malay Civilisation,Lembah Bujang